PEDRO BUKANEG: Father of Ilokano Literature

Pedro Bukaneg is one of the colorful figures in the history of the Philippines, particularly in the annals of Samtoy (ancient name of Ilocos, or Ylukon to the neighboring regions). His biography borders those of Philippine legends and folklores. From meager written sources and abundant oral traditions, biographers are able to weave the elusive strands of his life and remarkable achievements. They “rhapsodized” him as the first Ilokano man-of-letters.

BIRTH

SHROUDED IN OBSCURITY

Story-tellers compare him to the biblical Moses because as a newly-born baby he was found floating down the river by a woman; to the ancient Greek epic poet Homer, for he was born blind and grew up to be endowed with poetry and remarkable brilliance; and to Socrates, because he was not good-looking as a man but gifted with wisdom. As the first Ilokano poet, orator, musician, lexicographer, and linguist to appear in the limelight of history, whose name and deeds enhance the glory of Ilokandia’s literary heritage, historians and scholars has bequeathed upon him the title of “Father of Ilokano Literature.”

Many aspects of Bukaneg’s life are obscured by legendary mists, so that it is quite difficult to dissociate the historical Bukaneg from the legendary Bukaneg. Bukaneg might have been born either in 1591 or 1592. It is said that one day in March, 1592, a laundry woman found a little baby crying inside a floating tampipi (big basket for keeping clothes) along the bank of a stream (now called Banaoang River), a tributary of the big Abra River, which flows between the town of Bantay and Vigan, Ilocos Sur. She took the baby and saw it was a boy, ugly and blind. This story parallels that of the biblical Moses, who, was an infant found by an Egyptian princess (daughter of pharaoh) inside a basket floating down the Nile River. The only difference is that Moses was neither ugly nor blind. Evidently, Bukaneg was a victim of the brutal custom of destroying infants born with physical defects, practiced not only in Samtoy, but also in Sparta, Persia, and other nations of antiquity.

After saving the poor infant from a watery grave, the kind-hearted woman brought him to the parish priest of Bantay, who baptized him as Pedro Bukaneg. The name “Bukaneg” was said to be a contraction of the Ilokano phrase “nabukaan nga itneg,” meaning “Christianized Itneg (heaten).” History still has no information as to who were Pedro Bukaneg’s parents. Though there are folklores attributing that he was an offspring born from the forbidden union of an Ilokano mountain guardian spirit Emlang Ibabantay and an Itneg witch called Alupugan. As such, he was bestowed great wisdom but cursed with inauspicious appearance.

EXTRAORDINARILY

GIFTED

Fate had invariably given Bukaneg

certain wondrous qualities to overcome the handicap of blindness, such as

intellectual brilliance, retentive memory, sensitive musical sense, magnetic

eloquence, and gift for languages. He was brought up and educated by the kind

Augustinian priests in the convent of Bantay, a priory (motherhouse) for new

missionaries assigned to the missions of Ilokandia.

As Bukaneg reached manhood, he proved to

be a remarkable Ilokano who was well liked and appreciated by the Augustinian

friars. A born linguist, he mastered Latin, Spanish, Ilokano and Tinggian

languages. He possessed an extraordinary talent for assimilating all things

pertaining to theology, the Bible, and Spanish literature which his Augustinian

tutors taught him, and also the Ilokano folk songs and traditional legends he

heard from the old apos. Being a

romanticist, he composed poems and songs which were so tenderly sweet that he

gained fame among the Ilokano masses as a gifted troubadour.

Bukaneg was good not only in poetry but

also in oratory. He preached the Christian religion in the streets of Vigan,

Aringay, and other towns, and persuaded many of his people to discard their

beliefs. Large crowds of people always listened to him notwithstanding his ugly

face and blindness. Because of the numerous people he was able to convince to

change faith, he came to be called the “Apostle of the Ilokanos.”

The Augustinians friars recognized

Bukaneg’s many talent, but most especially his being adept as a linguist.

During the early days, Augustinian missionaries who arrived from Mexico and

Spain studied the Ilokano language in the Augustinian convent of Bantay by way

of preparing them for their apostolic labors in the mission fields of

Ilokandia. Bukaneg was their teacher in the Ilokano language. Aside from his

teaching, he wrote Christian sermons in Ilokano, translated the novenas and

prayers from Latin and Spanish into Ilokano, and helped in the preparation of

the first Ilokano catechism and grammar.

In 1606, Bukaneg helped Fray Francisco

Lopez (1565-1637), an Augustinian missionary-linguist, in the preparation of

the book titled Libro a naisurat amin ti

batas ti Doctrina Cristiana nga naisurat iti libro ti Cardenal a angnagan

Belarmino (Book Containing the Laws of the Christian Doctrine written by

Cardinal Bellarmine). This became the first Ilokano Catholic catechism, which

was printed in the Augustinian Convent of Manila in 1621 by Antonio Damba and

Miguel Seixo.

The first Ilokano grammar, also authored

by Fray Lopez, titled Arte de la Lengua

Iloca (The Art of Ilocano Language), and printed at the University of Santo

by Tomas Pinpin and Tomas de Aquino in 1627, was also made possible through

Bukaneg’s invaluable assistance, In the prologue of the book, Fray Lopez

admitted the considerable assistance given by Bukaneg. Some scholars even attributed the true authorship to Bukaneg. The book is now

considered extremely rare. One copy of it is preserved in the British Museum in

London. Later editions of this valuable book were printed, with certain

revisions, such as by Fr. Fernando Rey (1792), Fr. Andres Carro (1793), and by

Fr. Cipriano Marcilla (1895).

|

The Arte de la Lengua Iloca, 1627

Unfortunately, many of the poems, discourses,

fables, stories, compiled translated ancient scripts, sermon prayers, and other

works written by Bukaneg have been lost. It is believed that a large number of

linguistic works, poems, novenas, and prayers which were attributed to the

Spanish friars were really composed by Bukaneg.

BIAG NI LAM-ANG

The authorship of Biag ni Lam-ang (Life of Lam-ang), the famous Ilokano epic, was

attributed to Bukaneg by some historians and authors. This, however, is a

disputed issue. The epic poem containing 294 stanzas, about 1,500 lines, with

the syllables of each line range from six to 12, was chanted by the Ilokano

folks hundreds of years before the Spaniards arrived in the Philippines and long

before Bukaneg’s existence.

In fact, much-older non-Hispanized

versions of this epic as narrated in oral traditions do not contain names like

“Don Juan,” which was Lam-ang’s father in the 16th to 19th century versions.

The Spanish name “Don Juan” could have been chosen based on phonemics, as

according to older folk storytellers, the name of Lam-ang’s father was Apo

Nakaliwliwan Peggadan.

|

A Bronze Sculpture of Lam-Ang Fight a Crocodile,

Kapurpurawan Rock Formation, Burgos, Ilocos Norte.

The attribution of authorship to

Bukaneg, on the other hand, was partly in fact due to his role as translator

and interpreter. Being blind, he dictated the epic from memory to scribes at

the same time translating it into Spanish. Consequently, the Ilokano epic was

put into writing, revised with the incorporation of Spanish influences and

Catholic dogmatic infusions, and was preserved for posterity with him as the

storyteller. The earliest extant transcription of Biag ni Lam-ang, however, was from 1889. Nevertheless, we owe it to

Bukaneg that this priceless Ilokano popular epic was saved from oblivion.

A

WISE JUDGE

The Ilokanos also recognized Bukaneg as a

seer. They came to consult him whenever they were in trouble for they had

implicit faith in his wisdom. Even the Spaniards in the province look for him

for the guidance in their hour of need. An anecdote was told that one day the

Servant Don Nicolas de Figueroa, Spanish encomendero

of Narvacan and Bantay, was shot to death by arrows and the arquebus which he

was carrying was stolen. Shortly afterwards, a band of Tinggians were captured

near the scene of the crime and were taken to Bantay. One of them was believed

to be the murderer, but the authorities could not determine the guilty party in

as much as all of the accused refused to talk.

In the midst of their judicial

perplexities, the Spanish authorities called Bukaneg to help them in the trial.

When Bukaneg arrived at the scene, he asked that all the Itnegs be freed from

their bonds, explaining that “it was not right that all should suffer from the

deed of the guilty man.”

Bukaneg walked around the circle of

Itnegs who stood silently, betraying no emotions on their stolid faces. He

placed his right hand over the breast of each one, feeling their hearts throb.

After this seemingly strange ritual, he pointed one Tinggian, declaring him the

guilty murderer. Taken aghast by Bukaneg’s clever deduction, the Itneg broke

down and confessed. He was accordingly punished. His companions, who were set

free, returned to their village in the hills and related the tale of Bukaneg’s

strange power of second sight.

ENDURING

LEGACY

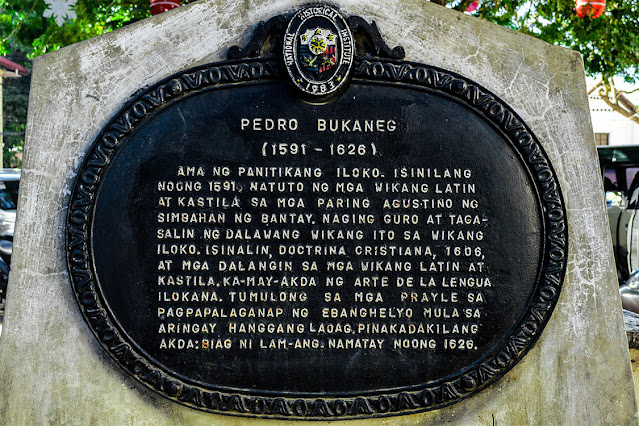

|

Historical Marker

for Pedro Bukaneg,

| Vigan, Ilocos Sur. |

Beloved by his people, Bukaneg died

around December of 1629. His death was mourned by his people who had come to

revere him as a man of remarkable wisdom and talents. Oral traditions narrated

the story of an entire region mourning his death. To his enduring fame and in

recognition of his literary legacy, the traditional Ilocano literary joust was

named as Bukanegan, after his name,

much earlier than the Filipinos of Tagalandia naming their literary joust Balagtasan, in honor of Francisco “Balagtas”

Baltazar (1788-1862), the laureated “Prince of Tagalog Poets.” In his honor, a

street inside the Cultural Center of the Philippines Complex in Pasay City was

named after him.

Whether legendary or historical, Pedro

Bukaneg’s greatest heritage is evident in the fact that compare to regional

literature that developed consistently from the Spanish Period, Ilokano

literature progressed at a pace as fast as that of the Tagalogs. In poetry, for

example, from the time of Pedro Bukaneg, we have seen the likes of Leona

Florentino (1849-1884), Isabelo de los Reyes (1864-1938), Mena Pecson Crisologo

(1844-1927), Leon C. Pichay (1902-1970), Godofredo Reyes (1918-2009), Jeremias

Calixto, Juan S. P. Hidalgo Jr, Jose Bragado, Reynaldo Duque (1945-2013), and

many more. Aside from poems, stories and novels published in the magazine Bannawag, numerous books being published

in Ilokano are clear indications of the wealth, as well as health, of writing

in the Ilokano language.